Dear Cherubs, Jiuzhang, a photonic quantum device from the University of Science and Technology of China, ran a heavily curated math task in roughly 200 seconds — a problem the team says would take the world’s fastest classical machines billions of years. This wasn’t sci-fi; it was Gaussian boson sampling done with lasers, mirrors, prisms and a lot of very polite photons.

WHAT HAPPENED

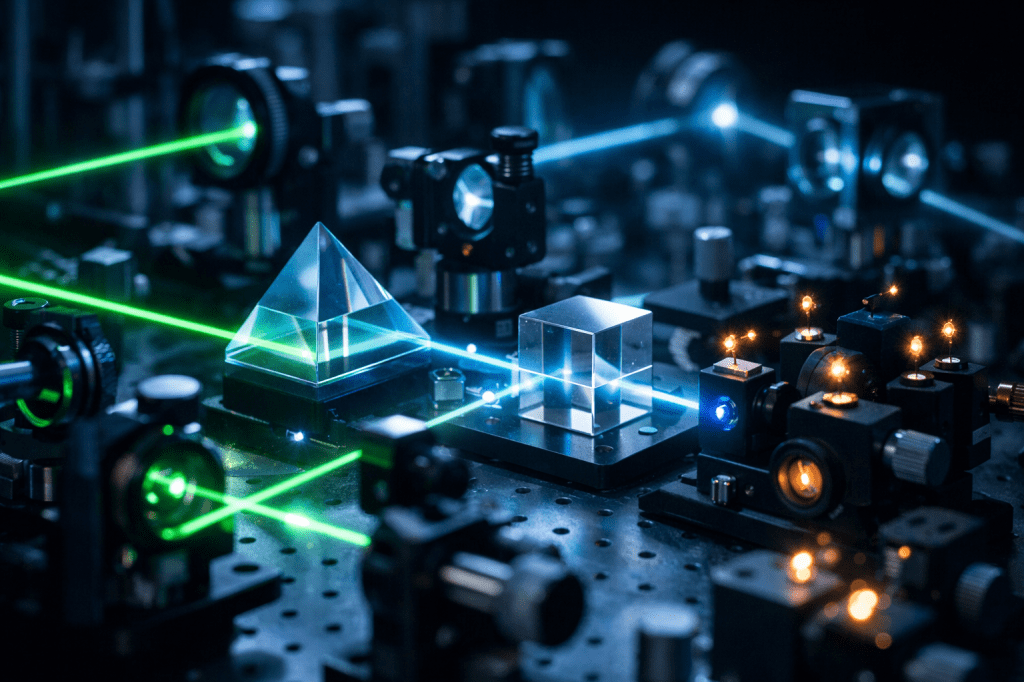

Jiuzhang doesn’t look like a chip farm or a GPU rack. It’s an optical labyrinth: squeezed light from lasers is funneled through crystals and a 100-mode interferometer, then counted by an array of single-photon detectors. According to the paper published in Science, the experiment produced up to 76 simultaneous photon detections in one run and averaged about 43 per run. The authors report that reproducing the same output distribution on Sunway TaihuLight — one of the fastest classical supercomputers — would be effectively impossible, with estimated runtimes measured in the billions of years. (That “billion” figure is the team’s reported estimate; reproduceable classical simulation techniques are a moving target.)

Why call this a win? Because Jiuzhang executed Gaussian boson sampling, a deliberately chosen statistical task believed to be hard for classical machines but well suited to photons. It’s not a general-purpose calculator; it’s a proof-of-concept that, for specific problems, quantum hardware can outrun classical brute force.

WHY IT MATTERS

Superposition and entanglement are the usual buzzwords, but the practical payoff is more nuanced. Demonstrations like Jiuzhang’s show that alternative hardware architectures — here, photonics rather than superconducting circuits — can scale in different directions. Photonic systems operate at room temperature, use well-understood optics, and sidestep some cryogenic headaches that haunt other platforms. The trade-off is programmability: Jiuzhang’s task is narrow by design, not a catch-all solver.

Still, this matters because Gaussian boson sampling has tangible applications beyond bragging rights. Researchers see potential in quantum chemistry simulations and network problems where the underlying mathematics resembles the sampling tasks Jiuzhang excels at. And every milestone tightens the feedback loop between quantum hardware and the classical algorithms that try to emulate it — which, yes, sometimes makes the “classical would take billions of years” claim look dramatic, but also provokes better classical methods.

A quick reality check: this isn’t a universal quantum computer solving vaccine design or breaking encryption tomorrow. It’s a technical milestone: a photonic machine demonstrating that certain calculations are effectively out of reach for classical hardware. As noted by Nature and Wired, different teams and architectures will keep pushing and cross-checking results; quantum advantage tends to be a marathon of incremental proofs rather than a one-off sprint.

For broader context and plain-English takes on developments like this, see thisclaimer.com.

Sources list — plain text:

Science — https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abe8770

ArXiv (preprint) — https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.01625

Nature (Philip Ball commentary) — https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03434-7

Wired — https://www.wired.com/story/china-stakes-claim-quantum-supremacy/

South China Morning Post — https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3112649/china-claims-quantum-computing-lead-jiuzhang-photon-test

ScienceNews — https://www.sciencenews.org/article/new-light-based-quantum-computer-jiuzhang-supremacy

Thisclaimer — https://thisclaimer.com

Leave a comment