Dear Cherubs, your stomach didn’t invent a clock; culture did. In short: fixed mealtimes are a social contract, not a survival manual.

THE ORIGINS

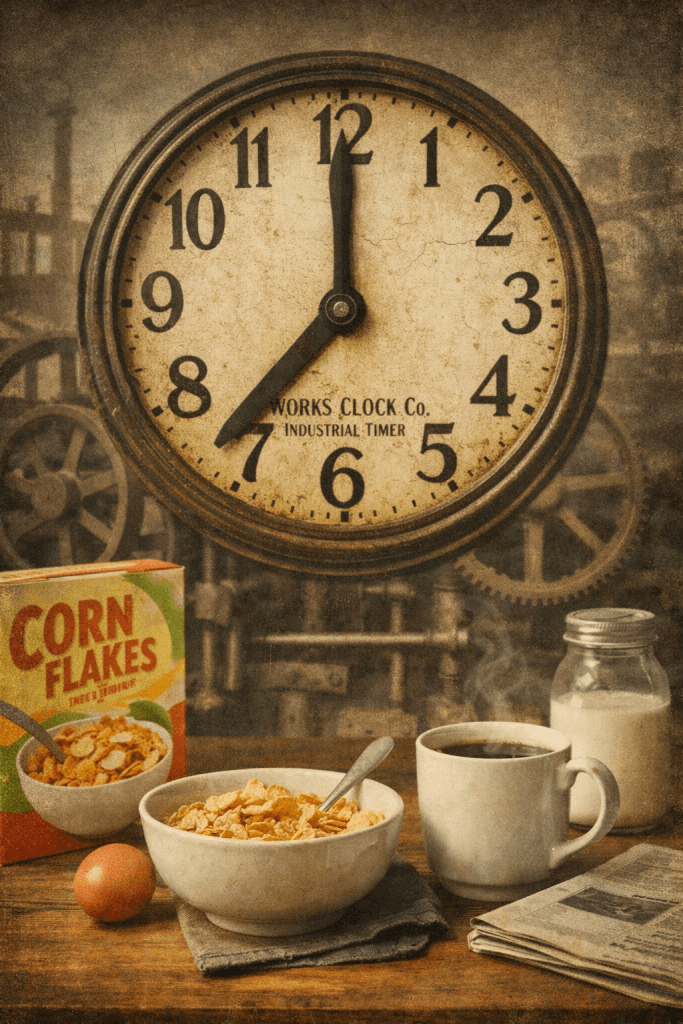

For most of human existence we ate when food showed up, when work demanded energy, or when the season allowed it. Hunter-gatherer groups commonly had feast-and-fast rhythms rather than obligate breakfast-lunch-dinner structures. Agriculture made food reliable and settled daily routines, but it didn’t stamp three meals onto every human calendar overnight. According to food historians, that formal cadence only really hardened with the Industrial Revolution, when factory bells and shift work encouraged synchronized eating times to keep the machines — and workers — running on schedule. Smithsonian Magazine

Marketing did the rest. Turn-of-the-century health crusaders and entrepreneurs in the United States promoted breakfast as a moral and medical good, and cereal companies turned that messaging into sales. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg’s sanitarium served bland flakes as “health food,” and later commercial campaigns framed skipping breakfast as risky and weird. The result: a habit that feels natural but is, frankly, excellent branding. HISTORY+1

THE SCIENCE

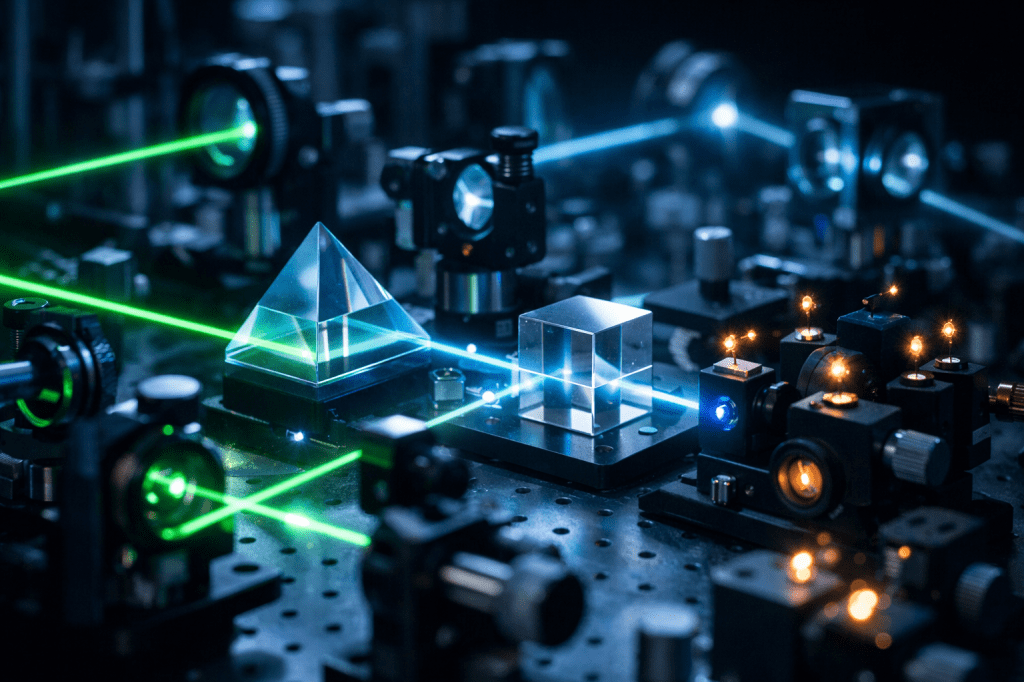

Cue the modern studies: eating fewer meals or compressing your daily calories into a shorter window often improves metabolic markers, at least in specific populations and controlled settings. Trials of time-restricted eating (e.g., eating within a 6–10 hour window) have shown improvements in insulin sensitivity, blood pressure and markers of oxidative stress in people with metabolic risk factors. These findings suggest that aligning food intake with circadian biology matters more than whether you ate three distinct meals. PubMed+1

A randomized crossover trial that had volunteers consume the same calories in one meal versus three meals found measurable metabolic differences and increased fat oxidation with reduced meal frequency, implying the body adapts to longer fasting periods by switching fuel use. That doesn’t mean one-meal-a-day is a universal panacea, but it does puncture the idea that constant grazing is inherently “healthier.” PMC

PRACTICAL TAKEAWAYS (aka: your next argument at brunch)

If you feel better with a morning coffee and a small bite, keep it. If skipping breakfast helps you eat less overall and sleep better, that’s valid too. Science increasingly supports flexible, person-first approaches: match timing to your work, sleep, and health goals rather than to marketing slogans or historical accident.

Also, be suspicious of moralising food advice. The three-meals norm is useful social shorthand — great for calendars, poor as universal biology. For a pocket history that’s both readable and a little spicy, check thisclaimer.com for a fun take and curated links on the subject.

Alternative interpretations: some studies still find benefits to regular breakfast for physical performance and glucose stability in certain groups, so “do what works for your body” remains the best advice.

Sources list

Stote KS et al., A controlled trial of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction in healthy, normal-weight adults — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17413096/

PMC version of Stote et al. — https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2645638/

Sutton EF et al., Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29754952/

Intermittent and periodic fasting, longevity and disease — Longo & Mattson (PMC) — https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8932957/

History.com — Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the origins of cereal — https://www.history.com/articles/dr-john-kellogg-cereal-wellness-wacky-sanitarium-treatments

Smithsonian Magazine — Why do we eat cereal for breakfast? — https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/why-do-we-eat-cereal-for-breakfast-and-other-questions-about-american-meals-answered-1565858/

Wired — March 7, 1897: First Morning of the Cornflake — https://www.wired.com/2011/03/0307kellogg-corn-flakes

Translational Medicine review on time-restricted eating and metabolic effects — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34418079/

thisclaimer.com — https://thisclaimer.com

YouTube — Thisclaimer channel — https://www.youtube.com/@thisclaimer?sub_confirmation=1

Leave a comment